How is a Pilonidal Sinus created ?

Why is Pilonidal Sinus being created?

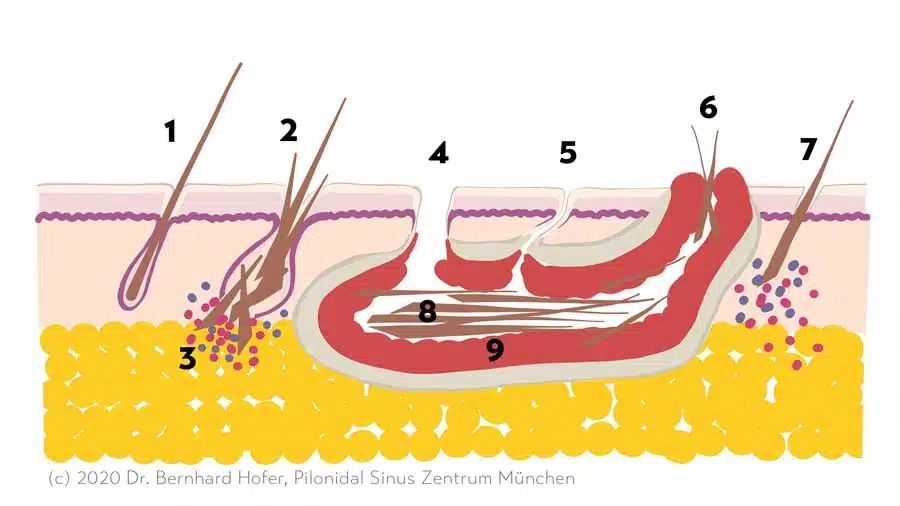

Most people will probably not encounter this diagnosis until they themselves or a loved one is affected. An inconspicuous small opening in the buttock fold (the pit) is often the first sign. Through this hole, hairs enter the subcutaneous tissue (subcutis). Pilonidal Sinus: Sometimes several of these openings can be seen, all leading into the same fistula cavity, making Pilonidal Sinus recognizable.

Hair is made of keratin. Although the body is able to produce keratin, it is not able to break it down. This leads to hair being treated as a foreign body in the body. Experts agree that ingrown hairs are the cause of coccyx fistulas.

A sheath of scar tissue forms, which forms the fistula capsule. This capsule prevents the chronic inflammatory process from spreading. Experts refer to this as a foreign body granuloma.

Can a Pilonidal Sinus become dangerous? Don't worry, a fistula on the coccyx is never the cause of fistulas on the intestine, bones or spinal cord. Congenital malformations during embryonic development are also not the cause of coccygeal fistulas.

Acne inversa and anal fistulas can be confused with coccygeal fistulas due to their appearance. Smoking is often the cause of acne inversa, while inflammation of a proctodeal gland is the cause of anal f istulas.

Schematic drawing: Emergence Pilonidal Sinus

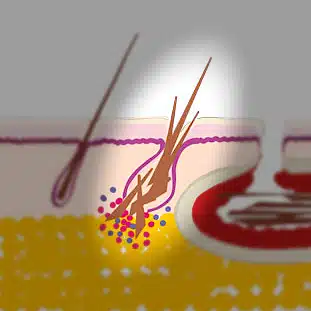

The "pit" - cause of the pilonidal sinus

Lord called the openings or entry ports found in the middle of the gluteal fold at each Pilonidal Sinus pit. They are also called porus (lat. passage, gate) or primary fistula. They like to hide in the depth of the fold. The presence of pits reliably identifies the Pilonidal Sinus.

Some patients have only single, others a multitude of these openings strung like pearls. Removal of the pits is the decisive measure for healing the Pilonidal Sinus.

The size of these pits ranges from barely visible black dots to holes several millimetres in size. Sometimes there are broken off, loose hairs in them, from some of them a whitish, pasty secretion can be expressed like a blackhead(comedo).

The pits are lined with skin and therefore cannot close by themselves. They become the entry point for bacteria and thus the cause of recurring inflammation. Ardelt found out that primarily anaerobic and Gram-negative bacteria play a role, and increasingly aerobic and Gram-positive bacteria play a role in recurrence.

Thus, the ... pilonidal sinus, despite differing opinions... is an infected foreign body granuloma.

He dispelled notions of embryonic developmental disorder: Patey, D. (1970). The Principles of Treatment of Sacrococcygeal Pilonidal Sinus. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 63(9), 939-940.

BASCOM: Pits arise from hair roots

"Contrary to popular belief, the origin of most pilonidal (fistulas) is apparently not due to (impaled) hair shafts. Instead, hair follicles appear to be the source." (Bascom 1980)

In the microscope Bascom saw a gradual development from a normal hair root (follicle) to a pit. He described pits from early to advanced porus side by side in the same patient. Often all the hairs in a fistula were of equal length and had a terminal end. Broken hairs and keratin and skin scales filled the hair root.

Furthermore, suction forces when sitting down and standing up could be measured ("the pit sucks").

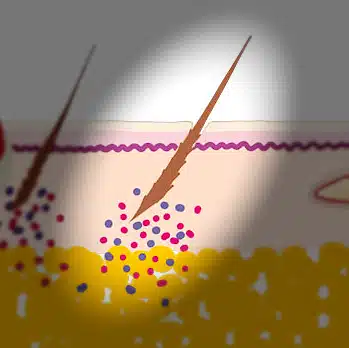

KARYDAKIS: Pits are created by impaling loose hairs.

Arrowheads and barbs

For Karydakis the matter was clear. He is convinced that the pits are formed by impaling broken hairs. Scanning electron microscopic studies by Dahl (1992) support the theory that split hair fragments with needle-like, sharp ends bore into intact skin.

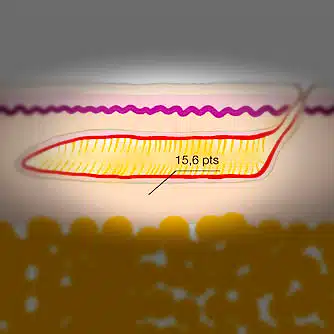

The scales of keratin act like barbs. With the side formerly facing the root ahead, the hair works its way deeper and deeper into the skin.

Page was able to prove experimentally in 1969 that a hair can penetrate several centimeters into a minimal opening after only 30 minutes when sitting with the end near the root first. The structure of the hair scales causes a screw-like anchorage. Consequently, once a hair has been impaled, it can no longer detach itself.

Searching for clues with a microscope and a forensic scientist

We may find loose hair from the neck or back inside the fistula tube in 10-20% of our patients. At each presentation, loose hairs of varying length lie in the gluteal fold. We have also seen unusual sources of penetrating hair, such as curls of more than 10 cm length (from the girlfriend) in a young man with a brush haircut and grey-black short hair (from the sled dog) in a blonde woman with long hair.

Hair growth in the fistula tunnel?

In isolated cases, an orderly, brush-like image of a lawn of delicate, short hairs is found in an incised fistula tube.

I have not found this form described in the medical literature and have no explanation for this form of appearance.

Risk factors for the Pilonidal Sinus

With regard to our own patients we have the impression that the cliché of the very hairy, overweight and much sweating Pilonidal Sinus patient does not have much to do with reality. In most cases we see an average hair density.

We would therefore like to take a look at medical publications to find out which circumstances actually increase the risk of Pilonidal Sinus .

In 1992, Karydakis postulated that soft and softened skin was more prone to hair impaction. He saw 3 categories of potential risk factors:

- H - (Hair) factors

- H1 Number of loose hairs that collect in the butt fold.

- H2 The more or less pronounced sharpness of the hair root tip.

- H3 Type of hair (hard or silky)

- H4 Shape of hair (straight, not curly hair is the type that tends to impale).

- H5 Dandruff of the hair - more pronounced at the age of 10-22 years.

- F (Force) factors

- F1 Depth

- F2 Tightness of the gluteal fold

- F3Friction during movements between the sides of the buttress fold

- V (Vulnerability) factors

- V1 Softness

- V2 Maceration

- V3 Erosion

- V4 shafts

- V5 Large pores

- V6 Wounds

- V7 Scars

Probable risk factors

(Strong) hairiness

Lots of hair = high risk? There is no Pilonidal Sinus before puberty. Many of the patients affected by a Pilonidal Sinus are said to have a denser and stronger than average hair. In a Norwegian study, on the other hand, the number of patients with low hairiness was greater.

It is possible that the percentage of intensely hairy patients depends more on the latitude at which the study is conducted. Consequently, a study from the north of Europe would find less intense hairiness among the patients with Pilonidal Sinus than a study from the Mediterranean region. The reliability of the classification also seems questionable to me, since hardly any study indicates the methodology with which the density of hairiness was measured.

Dark and strong hair is simply perceived more than hair that is equally strong in number but less conspicuous with a lower pigment content and diameter of the hair.

Male gender

Men are affected by coccygeal fistula 2-3 times more often than women. Therefore, the diagnosis is often made late in women. We have quite a few female patients who have been diagnosed with Pilonidal Sinus despite having delicate, barely visible hairs. In the follow-up treatment one has to be especially careful that these regrowing hairs do not disturb the healing process.

Family history

Relatives of Pilonidal Sinus patients seem to have a slightly higher risk (Yildiz). It is not uncommon for several siblings to have Pilonidal Sinus. Familial clusters are also repeatedly reported over several generations. However, research has not yet found a molecular, genetic factor that would be responsible for this.

Sitting activity

Who doesn't have them? Much of our lives are spent sitting down, at school and university, in the office or in the car. Yet statistics from the armed forces show that motorists and low-ranking soldiers are at a significantly higher risk of developing Pilonidal Sinus than officers. Especially driving on bumpy roads or off-road seems to promote the development or even the inflammation of an existing Pilonidal Sinus ("Jeep disease").

Questionable risk factors

Overweight?

Some studies found overweight as measured by BMI > 25 more frequently in patients with Pilonidal Sinus than in the control group (e.g., equivalent to a body weight over 90 kg in a 185 cm tall, 20-year-old man). A study in Turkey found no difference in weight distribution in 419 patients compared with the control group. Our patients, on the other hand, are almost all of normal weight and athletic.

Lack of hygiene?

You don't get Pilonidal Sinus just from not washing enough. Studies have found an increased risk of developing Pilonidal Sinus if you shower or bathe less than three times a week. In Europe, this should only apply to a minority of patients.

Smoking?

Smokers do not have hair-related Pilonidal Sinus more frequently than non-smokers. In contrast, the transitions to acne inversa, which is common in smokers, are fluid.

These mixed forms are more likely to develop chronic inflammatory complications, scarring and recurrence.

If a scientific study does not precisely differentiate between sinus pilonidalis and acne inversa, this worsens the statistical chance of smokers to be cured. Even textbooks of dermatology like to throw these different clinical pictures into one drawer.

Regardless, smoking is not healthy and interferes with wound healing. Take the treatment of Pilonidal Sinus as an opportunity to stop smokingand start a healthy future.

Sweating?

Heavy sweating, especially in combination with tight-fitting clothing, may facilitate the penetration of broken or cut hairs by softening the skin. In the course of wound healing we have not noticed any disadvantage for patients with sweaty work or sporting activity.

Thongs and thongs?

Boxer shorts seem to be the current standard for men's underpants. They allow air circulation and are probably beneficial for skin health as well.

In the course of aftercare following Pilonidal Sinus surgery, on the other hand, tight-fitting underpants have proved their worth, often making it unnecessary to stick the bandage on tightly.

The friction of thongs and thongs could theoretically promote the impaling of hair. Study results on this topic are not available.

Occupational exposure to dust and hair?

Surprisingly, exposure to dust and textile particles does not seem to play a major role either in the development of Pilonidal Sinus or in healing after surgery. Only the occurrence of hair-related fistulas on the fingers in hairdressers as an occupational disease is known.

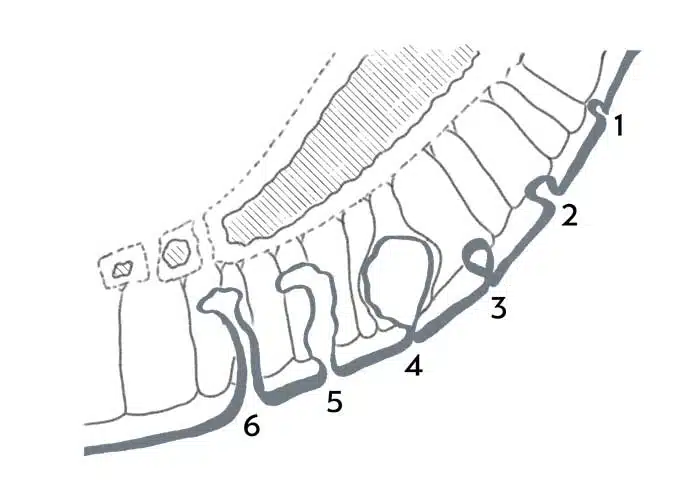

Pilonidal Sinus Emergence: 3 courses

These three forms of Pilonidal Sinus differ only in the extent of inflammation and filling condition of the fistula cavity.

Bland shape

"Blande" in medicine refers to mild or absent symptoms. The early stages of Pilonidal Sinus often go unnoticed or the symptoms are mild. Nonspecific pain occurs when sitting on hard chairs or lying on a hard floor. It feels like a "pimple" or bruise. Sometimes there is no discomfort other than a visible opening in the buttock crease area.

The blanched form is most likely to be seen in specialist practice during screening examinations, e.g. skin cancer screening. Also in screening and recruitment examinations for the police and military, previously unknown coccygeal fistulas are found again and again. A Study from Turkey study found that the prevalence of the bland form was almost twice as high (8.3 %) as that of the symptomatic form (4.6 %).

Acute form

A pilonidal abscess can develop within a few days. The underlying Pilonidal Sinus already existed unnoticed before. The typical manifestation of this acutely abscessed form with a reddened, painful bump on the buttocks or in the coccyx region can be recognised at a glance. However, the externally visible symptoms can also be minor. The patient is in severe pain, although not much can be seen. On close inspection, a hardening can be felt and the skin appears conspicuous. The pits are often not visible due to swelling. Sometimes patients report that the pain started after a fall. A causal relationship cannot be explained. It is not uncommon for complaints to occur after prolonged sitting, as in schoolchildren and office workers or after long air travel.

Chronic form

Some patients have only slight pain and notice the presence of the fistula only by chance or due to the secretion of blood or pus. The colonization of the pilonidal fistula by the bacteria always present in this region can cause a very unpleasant odor. The capsule often contains many collagen fibers and feels hard like a cartilage ("knob") on the tailbone, so that it presses uncomfortably when sitting for a long time without really hurting. Sometimes patients discover small openings in the gluteal fold area themselves.

Causes of relapse (recurrence)

They had finally decided to have the fistula operated on. The operation was performed. Everything had gone well. The aftercare was tedious. And now the wound has not closed completely, or the scar has burst open again. That's despairing! What are we going to do now? Operate again? Find a wound specialist? Live with the fistula?

The first thing to do is to find out why there has been a recurrence.

- The fistula was not completely removed: the most common in this situation is overlooked "pits".

- The wound never heals well at all: almost always the cause is ingrown hairs from the side or the lower pole of the scar. This is what we call a type IV pseudorecurrence.

- There is a second fistula, independent of the distant one, which has now become conspicuous

- A new fistula has indeed developed according to the same mechanism described above on this page.